Blog

Launch (or rabbit hole)

Launch (or rabbit hole)

Today, we are announcing the formal launch of the CRS and our website: conscious dot ai. The Consciousness Research Society (CRS) is a computer science research initiative focused on the development of artificial general intelligence (AGI). We have decided to take a unique approach that differs from other companies and individuals. Mainly, we believe that by better understanding the origin, nature, and mechanics of human consciousness, we will be able to build next-generation artificial intelligence. We strongly endorse using an interdisciplinary approach and freely share our work through online tools (projects).

Looking back

Technology has improved greatly over the last several hundred years. If we compare the year 1800 to 2019, we can see that these time periods are a world apart. Almost every major sector of the modern economy changed and life improved for billions of people. Technical innovation was strong, despite the disasters related to war. For example, humans went from riding on horses to walking on the moon, discovering genes to building bionic machines, and sending plain-text electronic messages to being passengers in self-driving cars.

Horse and buggy to the moon

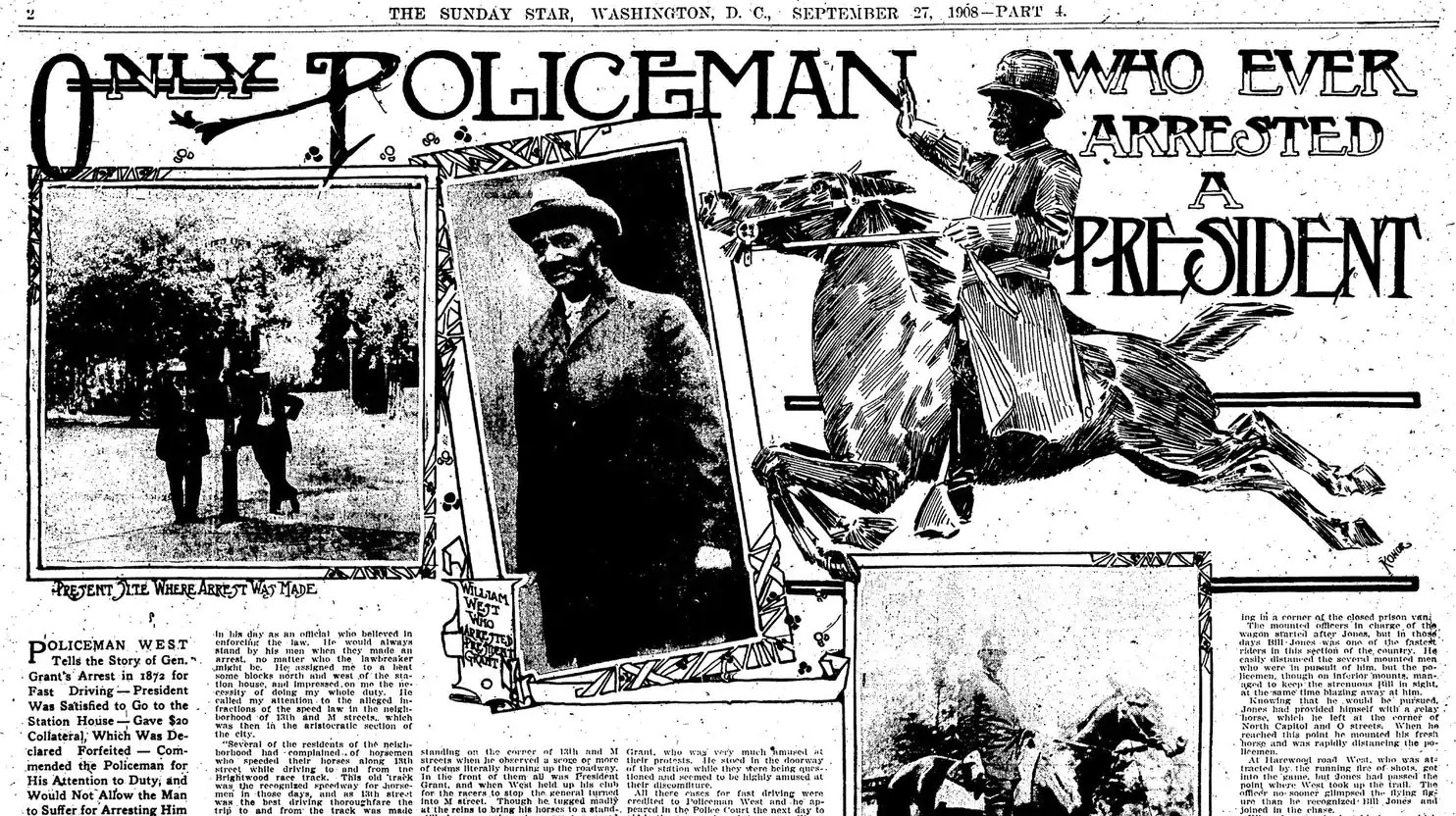

In 1872, Civil War veteran and Washington D.C. police officer William Henry West was reported to be located at the corner of 13th and M streets in Washington D.C.. As a re-telling of the story in 1908 explained,[1] West was told reports of speeding horse carriages the night before. That evening, West witnessed then President Ulysses S. Grant speeding and promptly stopped him—President Grant seemed to be a repeat offender. Grant was said to have been arrested and detained for his deeds, making off with paying a fine and a spot in the annals of the lighter side of history.[2]

Evening Star (September 27, 1908). A local Washington D.C. newspaper reported the story of Grant's arrest many years after the incident.

Evening Star (September 27, 1908). A local Washington D.C. newspaper reported the story of Grant's arrest many years after the incident.

We can't be entirely sure about all the details regarding Grant's arrest at 13th and M streets in 1872. However, we do know that Americans used horse and buggy for transportation up through the early 1900s. While trains had been previously invented and used for national transportation, horses were still a primary means of getting around. The picture, then, is extremely unfamiliar to our present experience in 2019—presidents riding horses, no planes, and certainly no Internet.

As the twentieth century encroached and ultimately turned over, the Gilded Age and its technical advancements roared with unprecedented ferocity—electricity, oil, cars, planes, Wall Street, skyscrapers, and more. In a relatively short chronological period of time, the landscape of the country changed. The United States of America rose to global prominence in the 1900s due to, among other reasons, its people, natural resources, and a number of critical technological advancements. As the major world wars unfolded, accelerated industrial engagement resulted in continued progress. By the time the cold war escalated, technological progress was, quite literally, out of this world.

On July 16, 1969, three middle-aged astronauts sat upward in an enclosed compartment of a space shuttle. As a timer ticked down to zero, they felt the vibration of the thrusters, its high-powered explosives, and the raw power of one of the world's most powerful rockets.[3] The three men waited an excruciating twelve minutes to get into the earth's orbit, likely knowing that their lives depended on many strangers they never met before. Several days later, Neil Armstrong would be the first man to step his foot on the moon, calling it "one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."[4] As Armstrong and fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin looked outward into the vastness of space, they saw Earth in full-form, oblate, and awesome.

Photograph of Earth (1969). The Earth is shown from the vantage point of the moon's surface, as shown by photos from the Apollo 11 mission. Source: NASA

Photograph of Earth (1969). The Earth is shown from the vantage point of the moon's surface, as shown by photos from the Apollo 11 mission. Source: NASA

Armstrong was a long way away from the corner of 13th and M streets.

The Apollo 11 mission was a major milestone for the United States of America, and all of humanity. More importantly, the accomplishment of going from horse and buggy to the moon primarily happened in less than one hundred years of focused innovation.

Genes to machines

In 1865, six years after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species,[5] Gregor Mendel anxiously waited for his turn to present his paper at a meeting of the Natural History Society of Brno, Czech Republic. Mendel presented his findings on Plant Hybridization, outlining how the traits of pea plants were not divinely allocated by gods; instead, his findings showed that trait inheritance was naturally determined.[6] Such findings, which are now known as laws of inheritance, were of the same order as mathematics. Mendel died in 1884 without much scientific acclaim or recognition for the gravity of his findings.

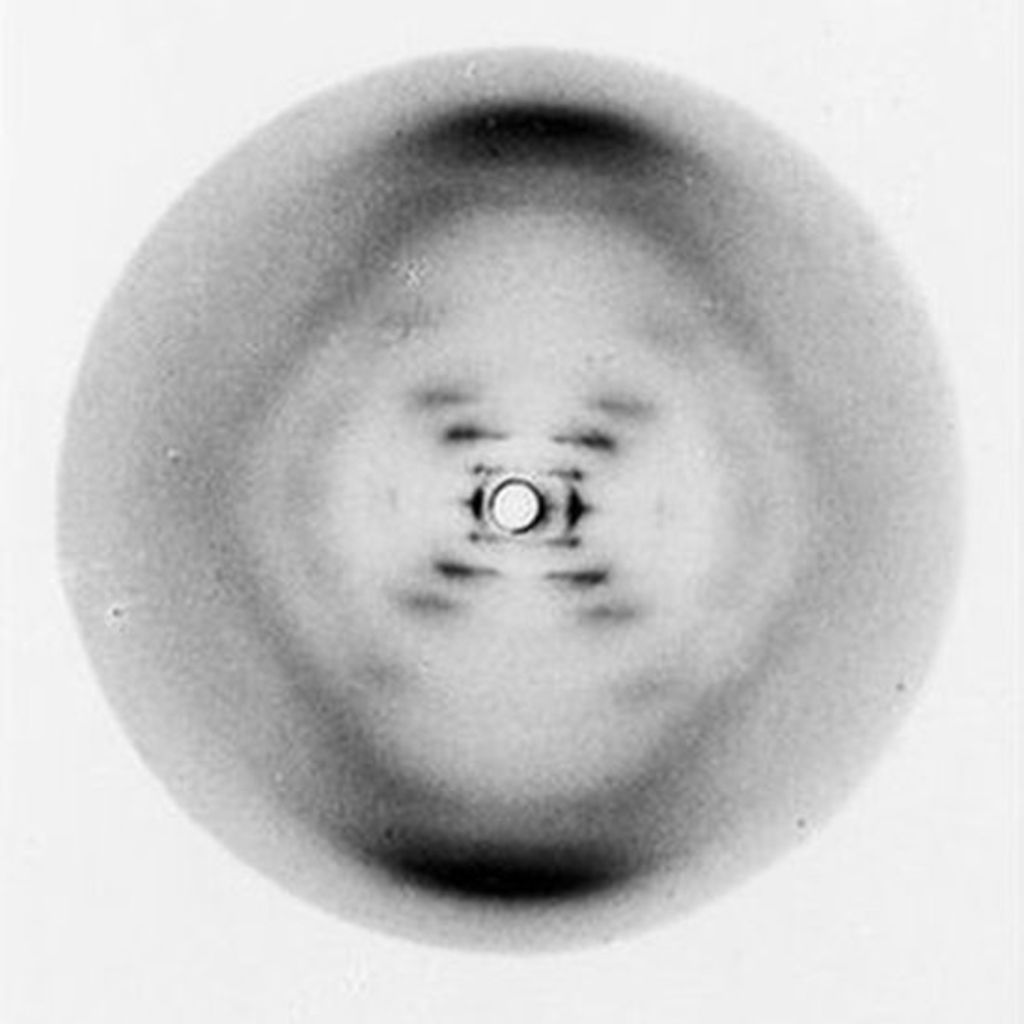

It would not be until 1952 that Rosalind Franklin used X-ray crystallography to take the first photograph of the double-helix structure of DNA—a discovery that James Watson and Francis Crick would take the credit for to win the 1962 Nobel Peace Prize.[7] Indeed, the discovery of DNA gave birth to the field of modern genetics.

Photograph 51 (1952). Rosalind Franklin's image of the DNA double helix.

Photograph 51 (1952). Rosalind Franklin's image of the DNA double helix.

Almost fifty years later, on July 5, 1996, the world heard reports that a sheep named Dolly was created as a result of a process that is generally called cloning.[8] While other attempts at cloning experienced unique challenges, the milestone was reached—humanity could play god, and it was not sorcery. The next twenty years saw attempts at innovation in regard to creating limbs and other artificial extensions of the human body. Lazarus did not quite emerge from his cave,[9] but humanity had accomplished an impressive feat, a feat made possible by the discovery of genes.

Internet to artificial intelligence

In 1971, programmer Ray Tomlinson would get credit for being the first person to send an electronic message using a modern email address with an @ sign.[10] However, the invention of email cannot be isolated to a single individual or instance in time. Indeed, Internet based mass communication systems required the cooperation of companies, scholars, scientists, and governments. The 1971 message was more of a collective milestone than an innovation. With the growth in popularity of the modern Internet in the 1990s through the 2000s, new and exciting technologies emerged. An interesting, but still premature, advancement was artificial intelligence. While much more still needs to be learned about this fascinating field, one readily available application seems to be self-driving cars. The concept of autonomous vehicles has been around for many years. But, artificial intelligence has been widely used and is seen as a core component of a truly autonomous vehicle, able to drive like a person. As of 2019, there are companies testing self-driving cars in states like Nevada.

Humanity has, without a doubt, accomplished a lot of technological innovation when it comes to transportation, industry, personal computing, biology, and other fields.

Here and now

Despite humanity's progress toward innovation and making sense of the world, a looming problem remains—why do we know so little about the vehicle that got us here in the first place? We are, in a transportation metaphor, talking about the human mind and its mechanisms. Psychology, when compared to other fields of study, is one of the least understood. A few basic examples will illustrate this point.

- Why does anesthesia work? Every day, it is estimated that some 60,000 patients undergo surgery whereby anesthesia is administered. We know (roughly) how it works, but we do not understand why it works. (read more).

- Why such different schools of thought? The current schools of thought within psychology are largely based on different core principles, contradicting each other at some critical points. As of yet, there is no commonly accepted grand unifying theory of psychology.[11]

- Why can't we agree on basic definitions? There is widespread disagreement on how to define extremely common terms that scholars, authors, and researchers use on a frequent basis. Some of these include intelligence, psychology, and consciousness.

While many fields of study have knowledge gaps, the one in psychology is, at its current state, breathtaking. A concerned reader may be wondering, rightfully so, what does this have to do with computer science? The lack of maturity within the field of psychology presents immense obstacles for the computer scientist trying to build next-generation artificial intelligence.

Let us consider this problem in simpler terms. The scientific community does not fully agree on a standard definition of intelligence. We do not know how intelligence, or the mind, fully works.

Given these premises, then, we must ask the following question: what, exactly, is a computer scientist building when she says she is building artificial intelligence? It would seem that the absence of a clear, standardized definition and understanding of intelligence makes it quite hard to translate such an obscurity into a concrete goal. That is to say, an undefined concept of intelligence is an undefined goal. This is the state of affairs within the field of computer science as of this writing.

Why don't humans understand intelligence, consciousness, and psychology with more clarity and precision?

There are many possible reasons why topics such as consciousness, intelligence, and psychology are highly misunderstood. For the sake of brevity, we will outline a few basic reasons.

- We do not have the technology to solve the problem. Some scientific discoveries require microscopes and telescopes, while others do not. Is artificial general intelligence out of our technical reach?

- It is an impossible problem. Some scholars have maintained that understanding human consciousness is impossible, in which case all energy toward its inquiry is poetry, not science.

- We are not meant to understand some things. Some would argue that we were not meant to understand particle physics so that we would not destroy ourselves through nuclear war.

- We are looking in all the wrong places. We may be investing energy and resources in areas that will not yield a sufficient answer.

- We need more time to do research. This is self-evident. If this is the case, then the answer must be "coming soon" or "in progress."

Whatever the reason is, we do know that artificial intelligence will not build itself, and humans seem to be the only ones capable of building it.

Looking ahead

The CRS is interested in unlocking exponential technological advancement through the development of artificial general intelligence. Where, then, do we begin in this ocean of disagreement, opportunity, and conflicting views. For one, we firmly believe that understanding human intelligence and consciousness is a solvable problem that we have the technology for. That is to say, it is a feasible problem that can be better understood with the current state of technology. We also believe that the answer is available, showing itself moreso than we think. We just don't seem to be looking in the right places.

To answer the question of how the CRS approaches this thorny problem, let us turn to a brief thought experiment that will answer the question plainly.

Imagine that you are the world's best computer software engineer. You have at your disposal an unlimited budget and unlimited resources in regard to robotics, human capital, and anything else. Your mission is to concretely define human intelligence in a way that everyone can agree on, without obfuscation or confusion. Additionally, with this definition, your task is to build artificial general intelligence so that it can solve problems that humans do not even know exist.

Having imagined this scenario of optimism, ask yourself: what is the last place where such a person would look; that is, what is the least likely field you should inquire in?

As an organization, the CRS believes that the last place such an individual would look would be the humanities, particularly as it relates to man's earliest written records.

This is, formally and officially, our starting point.

Our procedure, unlike others who are looking forward in the future, uniquely goes backward in time before considering what to build. Mainly, we are looking backward at the history of humanity to answer a simple, but loaded question: how did we get here? How did we get all... this? Our research journey, therefore, shall begin in antiquity, Mesopotamia and onward.

A fresh look at intelligence

Humans are a special animal. We can do things that other creatures cannot, and these abilities allow us to do things we were not designed to do–like visit the moon. The CRS would like to find out why and how humans are able to override their biology to do things that do not make sense in terms of survival. It would seem that this has a lot to do with what people call intelligence, a term that, as we mentioned, is still not clearly defined and agreed upon.

Our proposed roadmap starts with looking at the past and hopefully ending with building what is required for the future.

- Study ancient civilizations to find out how we got "here"

- Define what makes humans truly special in their mental faculties (i.e., intelligence)

- Extract the necessary initial conditions, precursors, and contingent requirements for extraordinary intelligence

- Share our research along the way

- When we're ready—build

That is what we are working on and why we are working on it. We are probably going to be wrong in most facets of our work, but that is a part of the process, and we have to love the journey if we are going to keep doing it day after day.

A rabbit hole?

Our approach may sound silly, even nonsense according to feedback from some reputable experts in the field of artificial intelligence. Unfortunately, this sharp criticism may be true; however, we will not know until we delve further into our research and find out. Studying man's historical origins for the purpose of artificial intelligence may be a waste of time, but it is something that no one else is doing.

Like young Alice, we are falling into the rabbit hole.[12]

Alice falling down the rabbit hole. In this coloring book inspired image, Alice is shown swirling down into the unknown.

Alice falling down the rabbit hole. In this coloring book inspired image, Alice is shown swirling down into the unknown.

At the very least, if our endeavor fails miserably, it will be clear evidence that this approach is not worth pursuing, and that may save someone else time in the future. Additionally, all our research will be available to the public so that other fields can make use of it.